The missing link of the “New Silk Highway” is set to finally be completed. Construction has begun on a new highway that will stretch from Russia’s border with Kazakhstan to Belarus, serving as a critical part of the China-Western Europe transport corridor—an infrastructure mega-project that has been described as the “construction of the century.”

Once completed, the China-Western Europe transport corridor is meant to be the primary nervous system of the Silk Road Economic Belt, the overland portion of China’s Belt and Road initiative. The corridor begins at the Chinese port of Lianyungang on the Yellow Sea and stretches along the Lianhuo Expressway, China’s longest road, to the Khorgos dry port on the border of Kazakhstan before moving through Russia en route to Western Europe. The corridor is meant to eventually combine road, rail and air transport hubs into a multi-modal ecosystem which could revolutionize the economic role of the central stretches of Eurasia and alter our paradigms of how goods are shipped between China and Europe. Ideally, this highway would allow trucks to travel between China and Europe in just eleven days, as opposed to 30-50 days by sea and 15 days by rail, making it the fastest overland option of the New Silk Road.

While the China-Western Europe transport corridor got its start in 2009, it was hamstrung by Russia’s reluctance to give its portion of the project proper attention and funding. For years, the corridor served as a high-speed transit route into the heart of Eurasia, rather than a bonafide “Silk Road” which properly connects the east with the west. Trucks would speed across China and Kazakhstan on one of the world’s most modern highways only to run aground at the Russian border, where they would meet head on with infrastructure of a more modest persuasion. However, the fortunes of this mega-project may soon change.

Dubbed the Meridian highway, Russia’s long-awaited portion of the China-Western Europe transport corridor is now under active development. It is to become a 2,000km toll road from the Sagarchin crossing point with Kazakhstan to the border of Belarus.

This new highway is slated to cost in the ballpark of $9.3 billion, with most of the financing coming from private firms rather than public coffers—although investors have sought $500 million of government backing to hedge against potential unforeseen political upheavals, such as the closing of borders. The main player behind the project is a Russian investment holding called LLC Meridian, a company that’s fronted by Alexander Ryazanov, the former deputy chairman of Russian gas giant Gazprom and current board member of RZD, Russia’s railway monopoly, who claims to already be in possession of 80% of the land the road is slated to pass through.

The Meridian highway is primarily being developed for cargo transport, and the main stream of revenue is expected to come from tolls, which Ryazanov estimates will take at least 12-14 years to recoup his company’s initial investment. However, the highway is also posited to generate a large amount of knee-jerk development along its route and create new jobs, in addition to reducing transport times from China to the west of Russia three-fold, according to the Russian Ministry of Transport.

One concerning aspect of the project is its geopolitical overtones. Jonathan Hillman of the Washington D.C.-based Center for Strategic and International Studies think tank, points out that the route of the new highway subverts Ukraine, which “would add to a series of Russia-led transport projects that limit Ukraine’s connectivity with the east.» Political objectives adulterating transport routes and countries battling their rivals with large-scale infrastructure projects are nothing unusual on the New Silk Road. The Baku-Tbilisi-Kars Railway, for example, takes a conspicuous long-cut around the contour of Armenia, further cutting the small country off from its neighbors and putting it on the outside of the trans-Eurasian cargo flows that are starting to trickle through.

Hillman also pointed out that Russia could improve the future of this project by removing glaring trade barriers in the Eurasian Economic Union. One of the biggest bottlenecks of the Belt and Road isn’t just the fact that there are gaps in key trans-Eurasian transport routes but Russian sanctions against the import and transit of many products that could otherwise be shipped overland between Europe and China, which has actually given rise to a competing new corridor that bypasses Russia to the south.

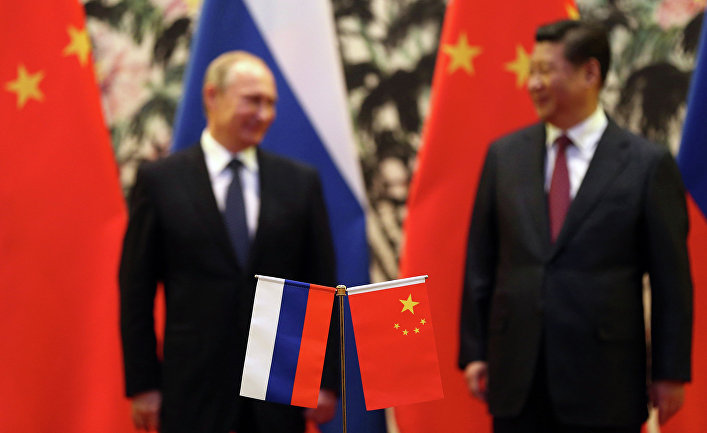

While Russia has always officially been a participant in China’s Belt and Road initiative and the broader New Silk Road, the country’s level of actual commitment has always remained in question. Spanning across much of the Eurasian landmass, Russian participation is necessary if China’s Belt and Road is to flourish. Two of the major overland routes between China and Europe pass through Russia, and Russian and Belarusian transport companies are often the workhorses behind the scenes that actually make these corridors function. However, Russia has carried out policies, including the above mentioned sanctions, which run directly against the «win-win» nature of the Belt and Road, and have been prone to delay or otherwise hamper the development of key infrastructure projects that must pass through their realm. The start of the Meridian highway is a good indication of where Russia is leaning as the Belt and Road picks up momentum.