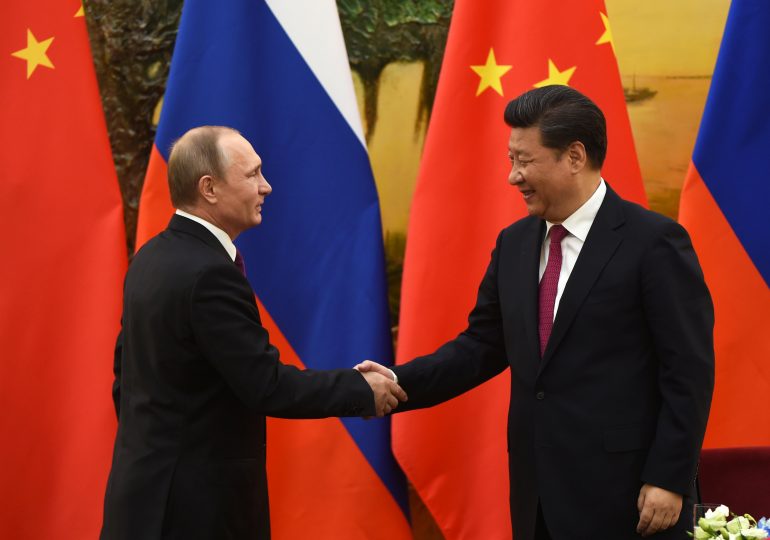

Early last week, Russia concluded Vostok-2018, its largest military exercise since the fall of the Soviet Union. It wasn’t just their size, however, that made the recent war games so groundbreaking. For the first time in history, 3,200 Chinese troops trained alongside some 300,000 Russians in eastern Siberia. Previously, the Kremlin had issued invitations to take part in such exercises only to formal military allies such as Belarus. Yet when asked at a press conference if the exercise made him worry about a possible Russian-Chinese military alliance, U.S. Secretary of Defense James Mattis was dismissive. “I see little in the long term that aligns Russia and China,” he said.

BUILDING THE BOND

Vostok-2018 was the culmination of a shift in Russian strategic thinking about China that gained momentum after 2014. Even before that, however, Moscow saw clear reasons for deeper engagement with Beijing. For one, both Russia and China care a great deal about preserving peace and tranquility along their shared 2,600-mile border. After a bloody two-day clash in 1969, both countries poured enormous resources into a costly military buildup along the border. In the 1980s, they moved to demilitarize border regions and ultimately settled a long-standing territorial dispute in 2004.

At present, both countries see their major security challenges elsewhere, and their shared desire to avoid creating yet another adverse relationship has been a stabilizing factor for relations. The Kremlin has its hands full with the wars in Syria and Ukraine, the impact of a growing NATO presence along its western border, and the ongoing U.S. defense buildup. For its part, China’s leadership faces growing tensions with Washington over security and trade issues, and various territorial disputes are straining relations with Japan, the Philippines, Vietnam, and other neighbors. Meanwhile, Beijing continues to pursue its long-standing goal of regaining control over Taiwan.

A second factor driving Russia and China closer is their economic interdependence. Russia is primarily an exporter of raw materials and tends to lack access to both advanced industrial technologies and capital. China, on the other hand, is a vast consumer of commodities, particularly oil and gas, and at the same time has catapulted itself into the ranks of technologically advanced nations with an abundance of capital to invest abroad. On paper, China looks like the perfect trading partner for Russia. Although Moscow was slow to tap into opportunities provided by the Chinese market, the global financial crisis of 2008 accelerated outreach. As a result, China has been at the top of the list of Russia’s trading partners since 2010.

Last but not least are shared political goals. Both regimes value stability, predictability, and the preservation of their hold on power above all else. And both countries, as permanent members of the UN Security Council, share a desire to shape the international order in a way that places sovereignty and limits on foreign interference in domestic affairs at its heart. This is visible in debates on various areas of global governance such as norms in cyberspace and control over the Internet, where Beijing and Moscow regularly support each other.

FROM MISTRUST TO ENTENTE

Despite these shared interests, the Kremlin continued to view China with apprehension until quite recently, primarily because of the demographic imbalance between Russia’s sparsely populated Far East and the bordering provinces of China. These provinces are home to some 120 million people, some of whom made their living as guest workers in Siberia. The Kremlin feared that if the Chinese migrants continued to flock to and settle down in Siberia, acquiring Russian citizenship in the process, the trend would lead to loss of territory in the long run. Another reason for anxiety was China’s theft of sensitive Russian military technology, such as the design for Su-27 fighter jets (the Chinese copy is labeled J-11B), which led to the slowing of arms sales in 2005. Finally, the rapid growth of Chinese influence through measures such as the Belt and Road Initiative has given Moscow cause for concern in Central Asia, which Russia has long considered to be in its sphere of influence.

The 2014 annexation of Crimea and the conflict in eastern Ukraine that followed dampened these concerns dramatically. Shunned by waves of Western sanctions, the Kremlin turned to Beijing for financial resources, technology, and export markets for Russian goods. Before doing so, however, the Russian government conducted an interagency study on the potential risks of closer engagement with China. The results helped mollify the Kremlin’s previous concerns and demonstrated that many of them were actually overblown. For instance, although the Chinese population in Russia had been unofficially estimated at more than two million, the government discovered that it doesn’t exceed 600,000, with over half of Chinese migrants located in European parts of Russia with the greatest employment opportunities, not the Russian Far East. Rising wages in China caused by a shrinking work force and high GDP growth rate, combined with the contraction of the Russian economy and devaluation of the ruble in 2014–15, have made Russia increasingly less attractive for Chinese workers.

The Kremlin also concluded that the Chinese arms industry is advancing by leaps and bounds thanks to massive investment in indigenous R&D. In less than a decade, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) will have little need for Russian-made systems, giving Russia a narrow window of opportunity to sell arms to China. Finally, Moscow came to believe that the growing economic footprint of China in Central Asia is inevitable. Deeper Chinese penetration into the region actually reduces incentives for these countries to seek export routes to Europe that might bypass Russia and create additional pressure on Russian exporters in its core market. Moscow is happy to live with Beijing making inroads into Central Asian economies as long as it formally respects the Eurasian Economic Union, a Moscow-led trade bloc that gives Russian companies preferential access to markets in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, and doesn’t challenge Russia’s self-proclaimed role as the region’s main security provider.

As a result of this shift in approach, Russia’s economic dependence on China has been growing since 2014, and Chinese banks have provided lavish loans for large Russian state–owned companies and the members of Putin’s entourage who are on various sanctions lists. This attempt to buy Russia’s loyalty is likely to succeed, since the Kremlin no longer believes a better relationship with the United States under President Donald Trump will materialize. The U.S. Congress’ near unanimous passage of a new wave of sanctions against Russia in August 2017 convinced many in Moscow that so long as Putin remains in power, relations with Washington will not improve.

Washington’s hostility to both regimes has been a major factor in the improving Russian-Chinese ties. The new U.S. National Security Strategy lumped China and Russia together for “attempting to erode American security and prosperity,” as did the Department of Defense’s new Cyber Strategy. Growing U.S. concerns about China and Russia predate the Trump administration, but they encourage the leaders of both countries to seek common ground. The massive Chinese-Russian exercise last week is a clear message to the United States and Europe: if you continue to pressure us with sanctions, tariffs, and military deployments, we will join hands and push back.

A DANGEROUS PARTNERSHIP

The Chinese-Russian security partnership has its limits, and it is important not to lose sight of them. Moscow and Beijing aren’t seeking a formal alliance, at least for now. Beijing doesn’t want to be dragged into a military confrontation with the United States as a result of belligerent or unintentional Russian missteps in the Middle East or Europe. By the same token, Moscow doesn’t want to be forced take sides if China clashes with other strategic Russian economic partners such as Vietnam or India.

Even in the absence of a formal NATO-style Chinese-Russian security pact, however, it would be a mistake for Washington and its allies to ignore the consequences of increased military partnership. Exercises such as Vostok-2018 improve interoperability between Russian and Chinese forces that could come in handy in regional hot spots such as Central Asia or the Korean Peninsula. They also improve trust and informal connections between senior officials—not unlike the ways Washington officials bond with their counterparts in Europe and Asia.

Enhanced trust between Russian and Chinese militaries may lead to growing cooperation and coordination in cyberspace, particularly when it comes to probing vulnerabilities in U.S. military and civilian communication systems. At a minimum, Russian and Chinese counterintelligence agencies are now believed to share sensitive information on CIA operations that are being conducted against them.

Right now, however, what matters to Beijing most is the increased flow of sophisticated Russian weaponry that will radically improve the PLA’s near-term combat capabilities. The advanced S-400 surface-to-air missile system that China purchased from Russia in 2014 and began installing earlier this year can allow Beijing to control all of Taiwan’s airspace, making defense of the island a much more challenging task for the Taiwanese air force and U.S. military planners. The S-400 will also help China achieve its goal of establishing an Air Defense Identification Zone, a space in which the Chinese military will have the authority to identify and control all foreign civilian aircraft, in the contested waters of the East China and South China Seas. Chinese purchases of the Su-35, Russia’s most advanced fighter jet, will serve the same purpose.

Conventional wisdom in Washington and other Western capitals ignores the degree to which shortsighted U.S. policies are pushing Russia and China closer together. Now would be a good time for U.S. policymakers to rethink a policy that antagonizes—at times needlessly—both of the United States’ principal geopolitical rivals and to think more creatively about how to manage a new era of increased competition among great powers.

Alexander Gabuev

Подписывайтесь на наш телеграм-канал. Инсайды о Китае — без лицемерия и пропаганды.