Censorship in the country is more complicated than many Westerners imagine.

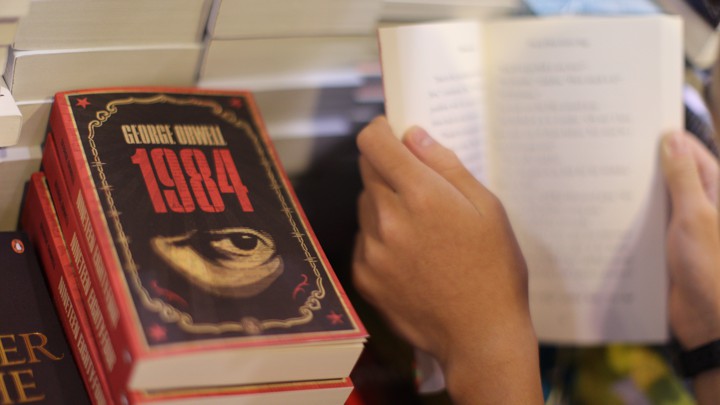

Last winter, after the Chinese Communist Party announced the abolition of presidential term limits, Beijing temporarily moved to censor social-media references to George Orwell’s Animal Farm and 1984. The government’s concern was that activists would use these titles to charge, in not-so-subtle code, that China was moving in a decidedly authoritarian direction. But censors did not bother to ban the sale of these texts either in bookstores or online. It was—and remains—as easy to buy 1984 and Animal Farm in Shenzhen or Shanghai as it is in London or Los Angeles.

The different treatment of these texts and their titles helps illuminate the complicated reality of censorship in China. It’s less comprehensive, less boot-on-the-face—as Orwell might have put it—and quirkier than many Westerners imagine.

Censors have banned books simply for containing a positive or even neutral portrayal of the Dalai Lama. The government disallows the publication of any work by Liu Xiaobo, the determined critic of the Communist Party who in 2017 became the first Nobel Peace Prize winner since Nazi times to die in prison. Again, for a time last year Chinese citizens could not type “nineteen,” “eighty,” and “four” in sequence—but they could, and still can, buy a copy of 1984, the most famous novel on authoritarianism ever written. Prefer Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World? They can buy that text, too, just as easily, although its title also joined the taboo list last winter.

Here’s the rub: Monitors pay closer attention to material that might be consumed by the average person than to cultural products seen as highbrow and intended for educated groups. (An internet forum versus an old novel.) As a result, Chinese writers are watched more closely than foreign ones. (Liu Xiaobo versus Orwell.) Another rule of thumb is that more leeway is given to imaginative works about authoritarianism than ones that specifically engage with its manifestations in post-1949 China. (1984 versus a book on the Dalai Lama.)

When a book crosses some lines but not others, censors generally use a scalpel rather than a sledgehammer. That explains the status of Brave New World Revisited, Huxley’s nonfiction work in which he argued that autocrats in the Soviet Union and China were combining the rule-through-distraction techniques outlined in Brave New World and the rule-through-fear methods detailed in 1984. Chinese readers on the mainland can find copies of this highbrow book by a foreigner pretty easily—but censors have surgically excised all direct references to Mao’s China.

These patterns may suggest that censors take a rather dim view of their audiences’ abilities—that they believe Chinese citizens are unable to draw a connection between the political situation Orwell described and the nature of their government (unless prompted to do so by a rabble-rouser on the internet). More likely, they’re motivated by elitism, or classism. Analogously, in the United States the MPAA slaps movies with an R rating if they depict nudity, but there’s no warning system for museums that display nude sculptures. The assumption is not that Chinese people can’t figure out the meaning of 1984, but that the small number of people who will bother to read it won’t pose much of a threat.

At an elite level, the rules in China have always been and still are more relaxed. When the first simplified character Chinese translation of 1984 was published in 1979, it was kept in a special section of libraries and bookstores that was off limits to most people. The laobaixing—the “common people”—couldn’t get their hands on the book until 1985. Today, graduate students can have much more nuanced and frank discussions about controversial periods in Chinese history than even college undergraduates.

There are three basic reasons for these disparities: elites must by definition have skin in the game in relation to the ruling party; the government knows it can’t really stop well-connected, highly educated citizens from acquiring the information they want, in part because they’re able to travel abroad and expose themselves to a variety of materials there; and the authorities are aware that a touch of liberty is often better than a boot in the face to keep people in line.

Western commentators often give the impression that Chinese censorship is more comprehensive than it really is due, in part, to a veritable obsession with the government’s handling of the so-called “three Ts” of Taiwan, Tibet, and Tiananmen. A 2013 article in The New York Review of Books states, for example, that “to this day Tiananmen is one of the neuralgic words forbidden—not always successfully—on China’s Internet.” Any book, article, or social media post that so much as mentions these words, the conventional wisdom holds, is liable to disappear.

Even when it comes to the “three Ts,” though, things are a bit less simple than they appear. Contra The New York Review of Books, references to Tiananmen, as a place, a tourist attraction, and so on fill the web in China. What’s verboten is reference to the killings that took place around there or to the date of the 1989 massacre, June 4. Moreover, although on the mainland no bookstore would dare stock a work by a Chinese author that mentions the massacre, there is some discussion of this taboo topic in the mainland translation of a biography of Deng Xiaoping by Ezra Vogel, a prominent American scholar.

The government’s approach to contentious individuals can be as surprising as its approach to contentious texts. On occasion, the government cracks down fiercely. The exiled writer Ma Jian, who has compared Xi’s China to 1984, told The New York Times that, “to Chinese readers, I am a dead man,” referring to the total ban on his books on the mainland. In July of last year, the political cartoonist Jiang Yefei was sentenced to six-and-a-half years in prison for “inciting subversion of state power” and “illegally crossing the border.”

But some writers, including Chan Koonchung, occupy a more liminal space. His most famous book, The Fat Years, is banned on the mainland because it invokes (indirectly) the collective, state-sponsored amnesia of the 1989 massacre near Tiananmen Square. Nevertheless, in October, he was allowed to host a BBC radio event in Beijing, which was open to the public. There he discussed, among other things, the debt his novel owed to Orwell and Huxley. Although the program was conducted in English, the audience was majority Chinese. And many audience members had managed to read this banned novel, whether by obtaining a copy from Taiwan or Hong Kong, or by downloading the pirated version that lived online for six months before censors scrubbed it away.

Chan said recently over the phone from his home in Beijing that, although he was “anxious” about the event, he hopes that his avoidance of specifically political activities will help protect him: “The only thing I do is write. I don’t join any groups or sign petitions. Apart from writing, I do nothing. That’s the only thing I do, and I have to keep doing it.”

Perhaps the most famous writer to live in China’s limbo between freedom and oppression is Yan Lianke, the subject of a recent New Yorker profile by Jiayang Fan. Yan lives in Beijing, teaches at the prestigious Renmin University, and is considered a hero in his home village in Henan, a poor, northern province. His most famous works include Serve The People!, a satire of the Cultural Revolution that features vivid sex scenes, and Dream of Ding Village, which deals with the taboo subject of the AIDS crisis that ravaged Henan in the 1990s. Both are banned on the Chinese mainland, although Fan notes that the ban is “de facto rather than official, and his less tendentious titles remain somewhat available.”

The “somewhat” is key: it is rare for the government to ban an author’s oeuvre in its entirety. Publishers have some leeway to make decisions on a case by case basis, and a publisher in Shanghai may come to a different conclusion than a publisher in Sichuan. These disparities are a result of individual judgement calls and the specific relationships between publishers and their local censorship authorities.

When the Berlin Wall came down in 1989, the first thing some East Berliners did was rush to fabled West Berlin department stores. One reason the Chinese Communist Party has outlived so many predictions of its imminent demise, in the wake of what political scientist Ken Jowitt dubbed the “Leninist extinction,” is that China’s leaders have been intent since the early 1990s to allow citizens at least partial access to consumer goods, including cultural products, that are available to their counterparts in other parts of the world. They know that if they keep the lid on too tight, they could stoke envy, and that envy could turn into a serious political problem.

Sourse: The Atlantic